"Listen!"

"Let’s go listen to the Great Nothing,” our guide suggested on one of the last evenings of our recent trip to Botswana.

We were in the Makgadikgadi, a place roughly the size of Switzerland and largely uninhabited by humans except on its fringes. Located in the middle of dry savannah adjoining the Kalahari Desert, the Makgadikgadi is the remnant of an extinct super lake that at 100 feet deep and nearly 31,000 square miles, once covered much of Botswana before evaporating millennia ago. Most notably, the Makgadikgadi is known by its series of salt pans, some of which are immense – the largest is 1,900 square miles. Deeper into one of these large, stark and flat, mostly waterless and extremely arid pans is where we were headed.

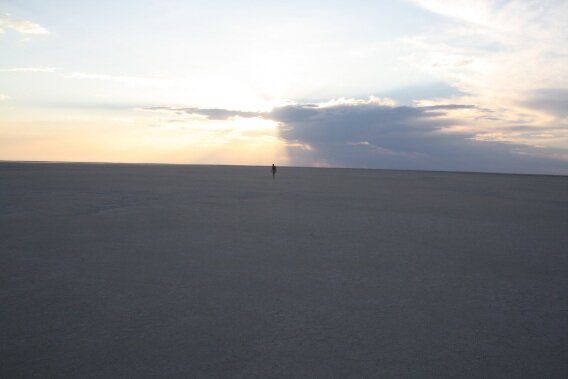

Of such large pans, someone once said, “you can drive at great speed and arrive nowhere.” And indeed, once we’d left behind the small green oasis of our tented camp set within fan-shaped palms and camel thorn acacia, bumped our way along the sandy ruts through a short stretch of scrubland and out past fewer and fewer patches of grassland, we sped along in our open-sided Cruiser on a salt-encrusted surface as flat as a billiard table and stretching as far as the eye could see. When at last we stopped, it seemed we had indeed arrived nowhere.

Here was a landscape unlike any I’d ever been in – the antithesis of our Maine island home or my native Midwestern Chicago. Getting down from the truck on a dry hard-packed surface that crunched beneath my feet but revealed little footprint evidence, I did a 360. Everywhere I turned, the pan stretched, endlessly it seemed, to the horizon. In all directions, it was possible to see the earth’s curvature.

I felt as if I were standing atop an enormous, overturned shallow bowl. Here, tone-on-tone minimalism had been vaulted to a whole new level. Within this vast space, there were no outcroppings, grasses, trees. Nothing hinted at sticks and thatch, much less mortar and bricks. I heard no birds, saw no critters. Oh, I knew that somewhere on the pans, unusual creatures who’d adapted to unimaginably harsh conditions somehow survived, and that after the brief rains, migrant zebras, sometimes in the thousands, trekked toward places where the pans briefly filled and grasses temporarily flourished. And that, seasonally, in years of good rains (which this was not), flamingoes in great numbers flocked to certain pans where for a time crustaceans hatched and algae bloomed. I knew, too, that separating some pans were desert patches where saline-resistant prickly salt grass thrived, and, improbably, magical-looking Baobab trees, the “upside down trees” with root-like branches and massive pulpy fibre trunks that could live for a thousand years. But in the “nowhere” to which we’d arrived, none of this was in evidence. It was as if we’d been transported to a separate universe.

Before me, the vast pan gleamed. Behind me, as I faced the lowering sun, my shadow cut dark and deep. We’d arrived in the “golden hour.” In the day’s last light that photographers and painters crave. We’d arrived, to quote poet Tony Hoagland in “Summer Dusk,” in the “hour of the evening with a little infinity inside….”

I began to walk in the direction of the soon-to-set sun. And now what struck me were not the visuals. As I moved away from the vehicle and my companions, I became acutely aware of sounds. Just my feet crunching the surface, my camera strap brushing against my side, a gentle wind blowing past my face and ears. I walked on further until the soft murmur of voices was no longer audible and the Cruiser had become a small, dark bump silhouetted against the horizon behind me. I felt compelled to walk even further, as though I were being pulled into the immensity, a feeling not of being swallowed up by the vastness but welcomed.

Finally, I dropped down and sat cross-legged on the pan’s crusty surface. The sky was starting to pull the curtain back on its nightly spectacle, rimming the curved horizon line with dusky rose, but it seemed the most natural thing to do was close my eyes. Now, I could better absorb what was palpable, what was extending beyond my brain’s synapsis-pinging recognition of it into something tangible, almost physical. It was the absence of sound. Or, rather, the presence of silence.

I’d come out to the Great Nothing and found a Great Something.

The deep quiet I was experiencing on the pans so exceeded any I often and desperately crave and willfully seek in a world increasingly amped up, cranked up and plugged in. Where an overload of noise, whether imposed upon us or self-induced, shuts out quiet, often at great costs to our ears and psyches.

Some linguists believe our oldest word is hist – “Listen!” Indeed, I'd been reminded a few times on our trip – usually as night descended – that hearing evolved as a warning system, to alert us 24 hours a day to what is afoot. How, for example, when a lioness is on the prowl, other animals and birds, even insects, cease their cheep and chuff and become silent so as to better listen. Our human ears take note of such cessation, too, whether we’re atop the Cruiser or in a suddenly flimsy-seeming canvas-walled tent. Is it any surprise that it seems quite natural and automatic for us humans to take joy, even comfort, in dawn’s reassuring symphony of birdsong or the raucous chorus of frogs in the dark? Perhaps our response to such clamor is automatic, a welcome relief that harkens back to our wary “animal selves.”

Out on the pan, I listened. The wind, the occasional crunch of my feet against the crusty surface whenever I shifted my weight – these were the only sounds discernible to my ears. Yet such absence did not feel like emptiness, a vacuum or void. Rather, it brimmed. With what, I can’t say. Maybe the rarity of it. To be in a place that though vast and open held such deep quiet. And held time, too. Not stilled time, nor, merely, its passage. But the presence of time undisturbed.

In the Makgadikgadi, the evidence of prehistoric man is abundant. Stone tools date earlier than the era of homo sapiens. Many experts believe our ancestors from which we all derive lived here. Thus, some say, coming to Makgadikgadi is not an arrival. It’s a return. A return to our ancestral home. And to a wind-sweeping-the-pan-silence in which reside sounds that my original brothers and sisters, and others since, could better detect and decipher. The evidence may be absolute that my ancestors dwelled here, rose up on their legs to look and listen. But who can say if, like me – or shall I say how many like me—sat cross-legged and puzzled over the silence, not, simply, its rarity, but what in it spoke of infinitude? And possibly resembled the original silence out of which the world arose?

Opening my eyes, I saw the “golden hour” was long past. The sun, a gold lozenge, was about to slip behind the horizon. It was time to head back. I stood, turned toward the Cruiser, and slowly crunched my way toward it. As I got closer, I could see that the wine had already been opened in our traditional “sundowner.” A few glasses were being raised in a toast. Voices drifted across the pan, the reassuring murmur of engaged conversation in which the welcome sound of laughter occasionally bubbled up.

Soon, a staggering plenitude of stars would fill the sky, prompting us to tilt our heads back in wonder, pondering as we always have the silent stars, their distance almost beyond our comprehension, but which, across the millennia, have given us direction, satisfied in constellation-making our need for connection, and inspired our stories. Stars like those of the Southern Cross which the indigenous Bushmen call the giraffe’s head. And Orion, said to be three zebras a hunter shot at and missed, his arrow just another star below – a mistake that meant the zebras galloped off each night toward the dawn’s horizon while the hunter, the “hungry star,” plodded wearily after them. And so would continue to do so, night after night. A silent resumption in the skies above this primordial pan to which I’d arrived, and returned.