To the Point

The list of ongoing projects at our Maine island house seems never-ending. This winter, we’re tackling a small writer’s cabin that will be built in the woods adjacent to our house. Though it’s intended to be a personal and quiet place where, hopefully, I can work less distracted, it’s also where I will house the boxes of books being shipped to Maine following our down-sizing move from suburban house to Chicago apartment.

This morning, about the cabin, Bob asked me, “So are you moving your pencils there, too?”

He means the large wooden trade sign and advertising pencils I’ve found over the years and which now are propped in a corner near my desk – the five-foot long replica of a classic, yellow Venus Super Velvet. The unembellished red pencil that by being “eraserless” suggests to me it’s a European model. And two shorter stubs not yet worn down to their ferrules.

Yes, at some point, they’ll find their way east. But not the real pencils in a brimming drawer within arm’s reach: a clutch of hexagonal FaberCastells No. 2, the yet-to-be-opened 3-pack of black Pentel mechanical pencils with white erasers and rubber grips, and the skinnier versions with a less comfortable grip but a perfect circumference to slide into the spirals of my preferred notebooks. And all of which I have in equal supply back east.

For years, pencils have been my tool of choice. A simple instrument that by the end of the 17th century, and through various evolutionary turns, achieved its present wood and graphite form, the pencil is a seemingly unremarkable object often taken for granted because it’s abundant, inexpensive, and universally familiar. But, of course, the pencil has significance. Sharpening our awareness to this fact is Henry Petroski, author of The Pencil. From him, I learned George Washington used a three-inch pencil while surveying the Ohio Territory in 1762, Thomas Edison preferred custom-made pencils, and Walden author Thoreau, though he failed to include a pencil when detailing his list of basics to carry into the woods, once worked for his father’s pencil factory, helping to perfect a mixture of graphite with clay. I also discovered the hexagonal shape of pencils is favored because they’re less expensive to produce – and have the added advantage of not rolling off my desk.

It’s long been conjectured that computers, not typewriters as earlier feared, would one day put pencils out of business, render them mere artifacts. But even in this age of laptops and tablets, pencils are still being manufactured in the billions world-wide. Impervious to gravity or water or a lack of power, a pencil can work anywhere anytime. For a typical user, a pencil yields about 45,000 words. There’s even a National Pencil Day, March 30, if you care to mark down – “pencil in” – the date. Using pencils, many of us take standardized tests, mark ballots, secure a twist of hair atop our head, and, with the eraser end as stylus, press the small keys of a calculator or phone. We twirl, tap, chew pencils. And I’m pretty sure that somewhere, at this very moment, an adolescent boy is attempting to hang them from his nostrils like tusks.

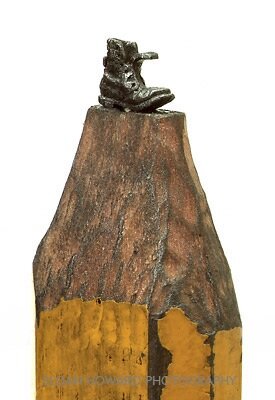

Not just the long-time tool of draftsmen, carpenters, architects and engineers, pencils also serve as metaphor and symbol. Of the thinking and creativity of artists and doodlers. Of the spontaneity of a child. Of thinkers and planners, whether as detailed sketches in the notebooks of Leonard da Vinci or of what is rattling around in the noggins of us lesser mortals and is made visible in small notebooks we carry in a pocket. Sometimes the pencil point itself becomes the art, as in the work of self-taught artist and carpenter Dalton Ghetti who, using pencils found on streets or sidewalks, carves the point with a sewing needle and a small, very sharp triangular blade, shaving away graphite fleck by fleck.

Often, following one of my readings, someone in the audience will ask if I write with a computer. Not to put too fine a point on it, but don’t we tap into a computer? But okay, yes, we also write – compose – on a computer. More and more of us do. But almost without exclusion, I begin writing with pencil and paper before transferring – tapping – the words into my computer. After that, I need a printed out hard copy from which, and again with pencil, I revise.

True, a pencil doesn’t move as smoothly or with as much flow as ink on paper. Petroski even likens graphite’s relationship to paper as more akin to that of sandpaper. I’m not sure I agree but I do appreciate – need – the more tactile connection a pencil offers. And the way its drag against page slows things down, leaves, perhaps, more time for the unconscious to enter, allows more space between hesitation and assurance. Before certitude solidifies.

I’m not alone of course. Many writers favor pencils. John Steinbeck was a voracious pencil-user, reportedly going through several pencils each day, partly because he discarded them once the metal ferrule crimping erasers into place touched his hand. Apparently not so for late poet Frederick Morgan. Following his death, photographer Gaylen Morgan in “Poet’s Pencils” commemorated her father by way of the pencil stubs he preferred and kept in small glass jars populating his desk. For the ease of revision, pencils are often favored. Vladimir Nabokov, claiming he had re-written every word he’d ever published, declared: “My pencils outlast their erasures.” Truman Capote, on the other hand, favored another method of revision: “I believe more in the scissor than in the pencil."

Certainly when working with a pencil, there’s a sense that what’s put down can be smudged, lost, erased. And that’s not always a bad thing. What I require in a pencil, whatever its type, is an eraser tip, an innovation not patented until the mid-19th century and a vast improvement over bread crumbs (seriously) reportedly favored for that purpose until then. Just as a computer’s delete key is – should be – our friend, the eraser can make short work of a hastily scribbled line in an angry note or on the page of a writer-friend’s manuscript I’ve agreed to edit but upon re-read is so illegible, further evidence of my handwriting’s decades-long devolution, it is itself in need of revision.

I confess: I write in books. I’m an annotator. A maker of marginalia. And for this, I’m sometimes in need of an eraser. Like when I lend out a book and I recognize that my notes resemble what Billy Collins in his poem “Marginalia” referred to as “skirmishes against the author/raging along the borders of each page.” Or as I discovered in advance of our move, when I assembled the books I planned to donate to a local non-profit and sought to erase the bulk of my marginalia, succumbing to the notion that annotated books are damaged goods, no more than spray-painted graffiti on a wall, but proved so vast a task I had to call in an arsenal of Pink Pearls and Magic Rubs.

Not that I plan to cease with my marginalia, what to my mind is an interaction with a book, a type of conversation, even if just in checkmarks, exclamation points, asterisks, or underlining that on its own is open to interpretation: Good? Bad? I like this? I object? For me, annotation has also served as a type of apprenticeship – noting how a scene is structured, what details have been chosen to serve the whole. Such pausing to notice and to notate encourages slow reading, a careful parsing that writer Benjamin Percy, a self-confessed mapper of a story’s architecture and marker of books, likens to spooning your way through a fine crème brulee that might be hiding a razor blade.

Since our move, I’ve regretted not taking from our former house the pencil sharpener screwed into the wall near the laundry tub in our basement. The old hand crank kind of sharpener with those adjustable holes accommodating a range of pencil sizes. Each time I used it, my hands circling the wheel, I was returned to my grade school, to the promise a freshly sharpened pencil held at the start of each day, and to forever fidgety Rodney in the fourth row who at least once daily asked permission to get out of his seat to sharpen his pencil and returning to his desk never failed to make some small goofy disturbance.

It’s too late for that sharpener to make its way into my new writer’s cabin. But yes, pencils will be transported there. Meanwhile, the process of getting the cabin built has many parts – some trees to be cleared, a power line to be brought in, concrete foundation posts to be set. And as the list grows long, I’m writing it all down. With, of course, a pencil.